| By Rivka Hodgkinson

Understanding Section 319 and Its Importance

Nonpoint source pollution—runoff from farms, roads, and urban areas—is the leading cause of water quality impairments across the United States. Section 319 of the Clean Water Act gives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority and resources to help states address this challenge.

Why Section 319 Matters in Michigan

Michigan’s lakes, rivers, and streams define our landscape and support tourism, agriculture, and recreation. Eliminating Section 319 funding in the EPA’s FY 2026 budget would severely undermine efforts to protect these water bodies. Over the past 10 years, Michigan Conservation Districts have received more than $11 million in Section 319 grants, leveraging $4.7 million in local match to implement watershed projects statewide. These projects deliver measurable improvements for water quality, public health, and local economies.

Impact of Section 319 Funding in Michigan

The statewide investments have supported community-led projects across numerous counties, including:

Clinton County

In Clinton County, conservation progress in the Maple River watershed has come from patience, consistency, and close collaboration with landowners. Rather than relying on one-time fixes, local conservation work has focused on helping producers adopt practices that improve soil performance while reducing runoff over the long term.

Work in the watershed emphasized:

- Cover crops and no-till systems to reduce erosion and improve infiltration

- Nutrient management planning to keep fertilizers where crops need them

- Filter strips and field-edge practices to slow runoff before it reaches the river

- Targeted outreach to address pollution from failing septic systems

Efforts have centered on cover crops, no-till systems, nutrient management planning, and targeted field-edge practices. Over time, these approaches have helped stabilize soils, retain nutrients on the land, and reduce pressure on the river during storm events.

The results of Section 319 – supported conservation work in Clinton County are both measurable and significant, demonstrating clear progress toward long-term watershed restoration:

- kept out of the Maple River

- Significant reductions in phosphorus and nitrogen loading

- Broad adoption of conservation practices across agricultural acres

- Nearly 1,000 tons of sediment

Today, the watershed is approaching a point where phosphorus impairment may be lifted—an outcome that reflects years of steady implementation and growing landowner confidence. Clinton County’s experience shows how sustained investment allows conservation to move from participation to progress.

To learn more or partner on future projects, reach out to Kurt Wolf at the Clinton Conservation District.

Van Buren County

In Van Buren County, Section 319 funding has supported a comprehensive approach to protecting the Paw Paw River and Lake Michigan by preserving and restoring natural systems that filter runoff before it reaches open water.

Key outcomes include:

- Conservation easements placed on six properties to retain natural features

- 419 acres of wetlands permanently protected and 29 acres restored

- 14,433 acres of cover crops cost-shared with landowners

- 3,203 acres of no-till or reduced-till practices implemented

- 6,596 linear feet of riparian buffers installed

- Six water control structures constructed to manage runoff

- Two rain gardens installed

- 1,325 feet of streambank stabilized

These projects demonstrate how strategic investments in wetlands and soil health simultaneously improve water quality, support wildlife and strengthen local agriculture.

To find out how to get involved, reach out to Emily Hickmott through the Van Buren Conservation District directory page.

Kent County

In Kent County, Section 319 funding has helped the Conservation District partner with farmers on projects that protect local streams and rivers that eventually flow into Lake Michigan. These waterways, including the Rogue River, Mill Creek, and Indian Mill Creek, play an important role in keeping Lake Michigan clean and supporting fish and wildlife.

Over the past five years, Section 319 support has made it possible to complete conservation projects that are often too costly for landowners to take on by themselves. These projects include:

- Strengthening streambanks to prevent erosion

- Installing grassed waterways to safely move water across fields

- Replacing aging culverts to improve water flow and fish passage

- Stabilizing slopes and erosion-prone areas

- Installing fencing to keep livestock out of streams

These improvements have been completed at 11 locations across the county and have kept thousands of tons of soil and large amounts of nutrients from washing into nearby waterways. The results include cleaner water, healthier habitat for trout and other aquatic species, and stronger recreational fisheries that benefit local communities.

As Kent County Watershed Specialist Joel Betts explains, “EPA funding through EGLE 319 grants has provided us at Kent Conservation District with a unique opportunity to extend our impact working with farmers to specifically focus on improving water quality and fish habitat in important tributaries of Lake Michigan.”

For more information on Kent County initiatives or to speak with Erin Sloan‑Turner, visit the Kent Conservation District’s directory listing.

Montcalm County

![dc127d1d5fa6e9ca619cd8204912b4bb[1422049754].jpg dc127d1d5fa6e9ca619cd8204912b4bb[1422049754].jpg](https://www.gvsu.edu/cms4/asset/C171E200-A9E7-33B9-57544583AFC2C9D4/dc127d1d5fa6e9ca619cd8204912b4bb%5B1422049754%5D.jpg)

The Flat River Watershed drains 564 square miles across Montcalm, Kent, Ionia and Mecosta counties. It suffers from E. coli, nutrients, sediments and warming stream temperatures. The Montcalm Conservation District implemented a range of practices recommended by the Flat River Watershed Management Plan to reduce these pollutants.

Key achievements:

-

50 acres of conservation easements to protect high‑quality habitat.

-

1,284 acres of cover crops and 33 acres of no‑till adoption.

-

97 feet of natural shorelines, water‑ and sediment‑control basins covering 30.2 acres, and grade‑stabilization structures on 82 acres.

-

Water‑quality results: 67 tons of sediment, 120 lbs of phosphorus and 848 lbs of nitrogen prevented from reaching waterways.

-

Education & outreach: mailed 9,000 septic‑system flyers, hosted 8 septic workshops, 13 farmer‑led meetings and 3 field demonstrations. Updated 5 township ordinances and mapped 3,695 septic facilities to guide repairs.

Shiawassee County

Spanning 94,200 acres in Clinton and Shiawassee counties, the Upper Looking Glass River project tackled sediment, bacteria and nutrient pollution.

Practices installed:

-

10.8 acres of water‑ and sediment‑control basins and 23.1 acres of critical‑area stabilization.

-

33 acres of grade‑stabilization structures, 35.3 acres of conservation cover, 1.5 acres of buffer strips and 185 feet of natural shoreline.

-

Infiltration basins, rain gardens, bioretention cells and wildlife‑habitat enhancements.

Outcomes & outreach:

-

Reduced erosion by 3,044 tons of sediment, 2,580 lbs of phosphorus and 4,825 lbs of nitrogen.

-

Held five field days, three shoreline workshops, seven river/wetland programs and three septic workshops to build public awareness.

-

Updated five township ordinances and mapped 390 historic septic facilities.

Ottawa County

In Ottawa County, Section 319 funding has supported long-term conservation work in several priority watersheds, including Sand Creek, Crockery Creek, Bass River, and Deer Creek. These streams flow into the Grand River and Lake Michigan, making them critical to both local water quality and the health of the Great Lakes.

The Ottawa Conservation District focused on reducing runoff from agricultural land, stabilizing streambanks, and improving natural filtration before pollutants reach open water. Rather than relying on a single approach, projects combined soil-health practices, wetland protection, septic improvements, and targeted restoration work.

Key conservation actions include:

-

Widespread use of cover crops and conservation tillage to reduce erosion and nutrient loss

-

Installation of filter strips, riparian buffers, and natural shoreline plantings

-

Construction of water and sediment control basins, infiltration basins, and rain gardens

-

Replacement or repair of failing septic systems and upgrades to aging infrastructure

-

Streambank stabilization and culvert improvements to reduce sediment during high-flow events

Across multiple projects and phases, these practices have resulted in:

-

Thousands of tons of sediment kept out of streams

-

Significant reductions in phosphorus and nitrogen loading

-

Improved aquatic habitat and water clarity in tributaries leading to Lake Michigan

Ottawa County’s work demonstrates how sustained investment, paired with strong landowner participation, can deliver measurable water-quality improvements across large, working landscapes. By addressing runoff at its source and restoring natural systems that slow and filter water, these projects help protect downstream communities and the Great Lakes.

To learn more about conservation efforts in Ottawa County, connect with the Ottawa Conservation District.

Measurable Results

Other counties—including Huron, Isabella, Kent, Lenawee, Montcalm, Ottawa, Shiawassee, Tuscola, and several others—have implemented similar watershed management practices, demonstrating that Section 319 provides an extraordinary return on investment.

Across Michigan, Section 319 projects have:

-

Protected wetlands and natural areas to filter pollutants and enhance habitat.

-

Supported cover crops, no-till practices, and nutrient management on thousands of acres.

-

Stabilized eroding stream banks and installed structural controls to reduce runoff.

-

Educated landowners and communities through conservation programs, MAEAP verifications, and cost-sharing incentives.

-

Reduced sediment, phosphorus, and nitrogen loads that threaten water quality and fish habitats.

These initiatives not only improve water quality but also strengthen local agriculture, enhance recreational opportunities, and support the resilience of Michigan communities.

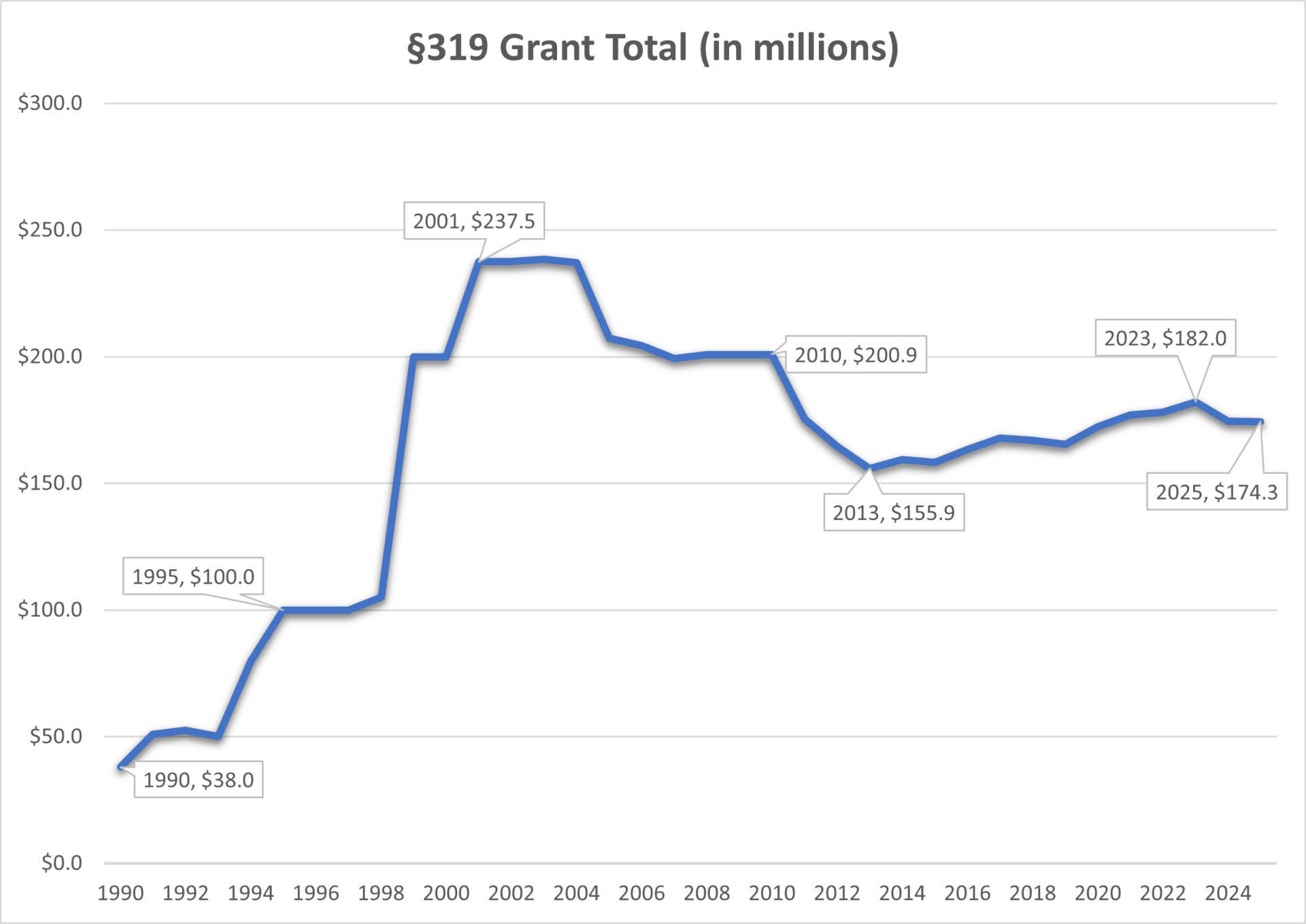

Why Sustained Section 319 Funding Is Essential

Eliminating or reducing Section 319 funding would halt vital progress and squander decades of collaborative conservation work. Without these grants, projects in the pipeline—such as Clinton County’s Upper Maple River watershed plan to remove a phosphorus impairment—could stall. It would also erode the partnerships built with farmers and landowners who have invested time and resources in adopting best management practices.

Maintaining at least $174 million in Section 319 funding in FY 2026 is critical to:

-

Continue successful nonpoint source pollution control projects across Michigan.

-

Support new community-driven watershed plans that address emerging water quality challenges.

-

Protect the Great Lakes and connected water bodies from sediment and nutrient pollution.

-

Preserve local economies reliant on clean water, from agriculture to tourism and recreation.

Michigan’s Conservation Districts have shown that Section 319 grant funding drives tangible, measurable improvements for our watersheds. By opposing the elimination of Section 319 in the EPA’s FY 2026 budget and supporting level or increased funding, policymakers can safeguard Michigan’s waters, public health, and economic future.

Join us in advocating for strong Section 319 funding to ensure clean water for Michigan’s communities. Our lakes, rivers, and streams—and the people who depend on them—deserve no less.